Erica Chow1, Bess Biscocho1, Kaylinda Tran1, Chaya Prasad MD MBA1

PNWMSRJ. Published online Oct 3rd, 2020.Abstract:

Studies of community gardens (CGs) have consistently demonstrated benefits through nutrition, mental health, income, and sense of companionship amongst community members. However, the use and distribution of CGs in low vs high income communities were found to not always be the same. In this study, we examined the distribution of community gardens (CGs) in disadvantaged communities and evaluated how socioeconomic status affects utilization of CGs. A review of the literature revealed 20 papers regarding CGs with consideration of income and social status with only six of these papers presenting self-reported income levels of its participants, while the remaining studies generalized the income levels of the individual gardeners. When utilization trends were studied between high- and low-income gardeners, it was found that higher-income gardeners identified their primary incentives for gardening were socialization, personal education and greater control of the quality and safety of their food, but lower-income gardeners cited food security and financial limitations as their priority in gardening. Additionally, low socioeconomic status neighborhoods that develop thriving CGs often find that the CG elevates neighborhood pride and perception, consequently creating a process of gentrification that drives away many low-income families that the CGs are meant to help. Finally, we summarize the recommendations of the authors for promoting CG access to low socioeconomic communities through policy, future research, and collaborative community efforts to minimize these disparities.

Introduction:

Community gardens (CGs) are green spaces developed and maintained by a surrounding community as a hub for collaborative gardening. Models range from individually maintained plots to communal efforts where multiple gardeners tend the same crops.1 There is increasing recognition of the benefits these urban green spaces can provide to gardeners and to the neighboring community.2-4 For example, CGs provide personal development, community cohesion, improved health, access to fresh foods, supplemental income, and environmental stability amongst many other benefits.5 A CG can improve community health by increasing availability and consumption of fresh produce.3 Other studies showed increased consumption of fresh fruits and vegetables were associated with lower intake of sugary drinks, sweets, and dairy products.6 Additionally, studies have shown that CGs also promote social and mental health by creating social connections and collaboration. This environment creates a sanctuary of safety, acceptance, and a greater sense of purpose for individuals.7 Low income limitations can force families towards unhealthy lifestyles, such as fast-food consumption, social isolation, chronic stress, and limited exercise. However, CGs can offset food costs or provide extra income from produce sale, thus combating food insecurities that consequently result in a series of unhealthy habits.8 CGs can also provide safe spaces, fresh produce, and a physically active and socially engaging pastime. However, limited resources such as transportation, time, and finances can make CGs inaccessible and unaffordable for some residents.9,10

This paper assesses the distribution of CGs in low-income versus high-income communities and highlights the factors that influence the locations and accessibility of these gardens. Considering the prevalence of literature that proposes CGs enhance the surrounding community’s social bonds, neighborhood pride, food security, and healthy food intake, our goal was to determine if this purported potential is realistic for the low-income communities that might benefit the most from CGs.

Methods:

The Science Direct database was searched for peer-reviewed articles that focused on CGs. The keywords used were “community garden” with “income.” Results were narrowed to peer reviewed articles in English. A preliminary review of the resulting papers was conducted to exclude results that were literature review articles, opinion articles, or not research studies. The reference lists of selected articles and any review papers were reviewed for additional articles not returned in the initial search for possible inclusion.

We included peer-reviewed, English articles with original research on one or more urban CGs that were organically developed by a surrounding community. CGs had to be a primary focus of the article, and that income level was investigated as a variable for inclusion. We eliminated papers that did not primarily investigate CGs, did not evaluate income or socioeconomic metrics, and cases where the CGs was specifically created for research. CGs from rural areas, or underdeveloped and emerging countries were excluded; only a couple papers existed for these criteria, so we could not make generalizations between urban areas or developed and Western countries, respectively.

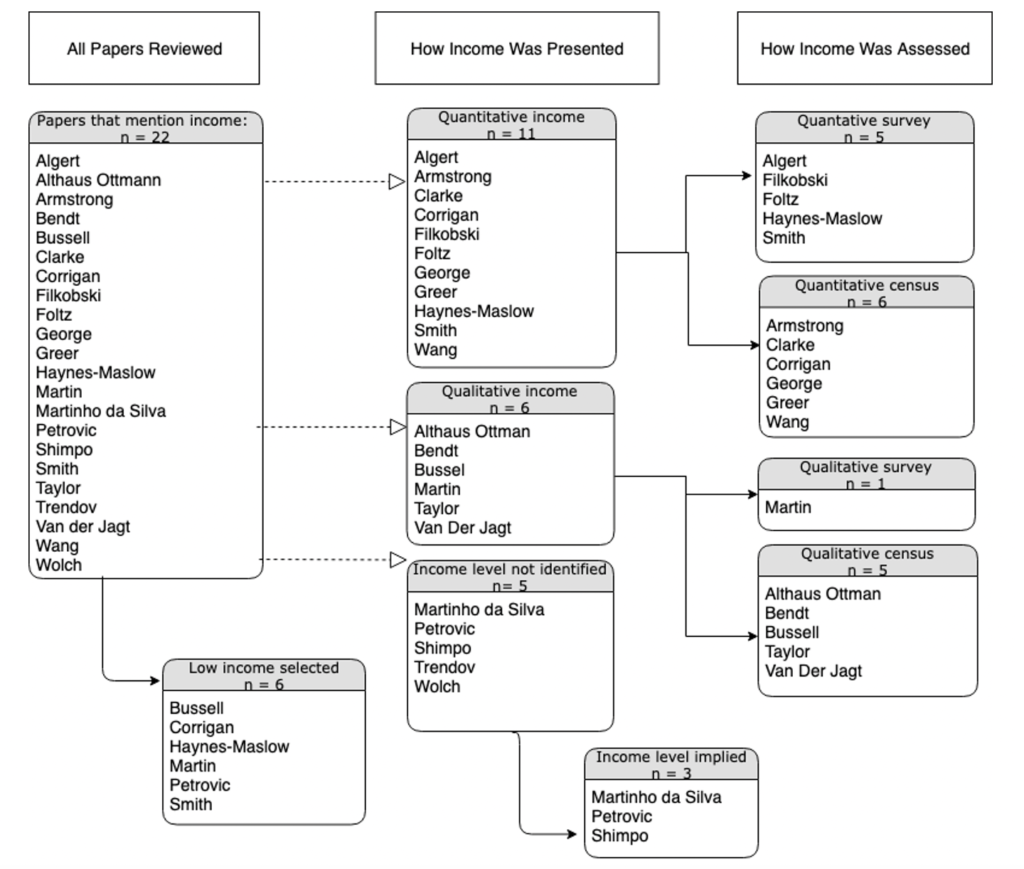

Included papers were sorted by whether income level was quantitatively or qualitatively described. Papers that explicitly described gardener income were further divided by how this information was attained (i.e. gardeners completed surveys, vs. inferred from the average income of neighborhood residents). See Figure 1.

Results:

The initial search resulted in 103 articles. Preliminary review narrowed this down to 32. Full article review resulted in 22 articles for inclusion.

Figure 1: shows how the papers that met review criteria were further categorized based on income and how this information was attained.

Measuring Income:

Our initial search resulted in 22 relevant articles. We found that 6 articles intentionally selected low income or minority-predominant CGs as a focus of the paper. Income was identified explicitly (either as a quantitative or qualitative metric) in n = 17 articles and was not explicitly given in n = 5 articles. Of these five, we found that in three articles the income levels of gardening participants were presumed from other metrics (i.e. unemployed vs highly educated). There were n = 6 papers that directly surveyed gardeners to ascertain income level, and n = 11 papers that used census data of the surrounding neighborhood as a proxy for determining income levels of the CG participants. The most reliable metric for assessing participant income was by survey; census data erred towards overgeneralization. Some papers presented income in low (below poverty), middle- and high-income categories, foregoing a ‘lower-middle class’ category which shares many of the challenges that low-income communities encounter.

Studies presenting quantitative income gathered through surveys were compared. Articles that intentionally selected low-income groups were excluded from this consideration, leaving three articles that showed a relatively equal number of higher and lower income participants. Algert reported CG participants in San Jose, CA had a below average monthly income of $4,900.11 Filkobski reports 34.5% of gardeners having below average income, and 29.3% above average.12 Foltz reports 26.5% as lowest-income gardeners, with highest-income participants accounting for an equivalent 26.9%.13 However, as only three articles fit this criteria we were unable to make generalizations about the greater distribution of CG users.

Utilization Trends:

Women of higher social class identified environmental concerns and a desire for quality produce as their primary motivation for gardening, while lower income women identified food security, limited income, and a desire for nutritious food. Both demographics agreed that personal development, pride in producing produce, and socializing were important motivators.14 Furthermore, Bussell and Armstrong both describe only a small percentage (12.5% and 10%, respectively) of CG participants that sold crops to supplement income. However, Bussell also identified a group of CGs operated by a non-profit refugee support organization that reported 84% of participants who sold crops for profit.5,15

Martinho da Silva identified a predominance of low income and unemployed applicants for CG plots. Unemployed applicants and the low-income group ranked food security as their primary reason for applying, with the unemployed group additionally ranking “access to organic farming” and “environmental concerns” as a low priority. Conversely, “highly-educated” applicants reported education, environment, and food safety as top priorities, with food security at the bottom.16

Discussion:

Differences in Utilization between Low Income and High-Income Communities

Low income communities were more likely to state the primary reason for gardening was to sell produce or use crops for food, reducing the financial burden of groceries.5,17 Van Holstein reiterates that higher income levels are inversely related to gardening for food and income supplementation, but parallels a desire to garden for leisure and personal gratification.18 CGs in Los Angeles, CA showed a positive correlation between income and plot sizes. Also, biodiversity of species grown in a plot increased with income; this was especially notable with ornamental plants, suggesting more disposable income for gardening.19

Higher income communities prioritized the social aspect of the gardens, such as formation of social bonds with other gardeners and community involvement. Personal development, personal accomplishment, and exercise were also prioritized. In general, CGs in higher income neighborhoods represent a recreational activity rather than a necessity, as these residents have more time and resources for gardening.4 Although lower income communities also appreciated camaraderie and personal development, this was viewed as a secondary benefit.15

Low-Income Accessibility:

Case studies of CGs in low-income communities were overrepresented in the literature. Specifically, several papers investigated CGs in low-income neighborhoods and third world countries, or over-sampled low income communities to ensure representation of these demographics in the study; thus, forgoing representation of the true distribution of CGs in urban areas.15,20 As a result, we could not accurately gauge the proportion of low-income CG participants to middle- and higher-income counterparts at this time. It also remains difficult to determine if socioeconomically disadvantaged populations are capable of making use of CGs despite the location of urban CGs in low-income neighborhoods and food deserts. 8 of 26 studies used location as a proxy for assessing income level. However, when considering factors such as limited resources and gentrification trends, as discussed below, we determined that living near a CG does not necessarily confer an equivalent level of access to gardening. Lower-income residents must overcome many barriers to gardening including limited time, social capital, knowledge, finances, as well as safety and transportation concerns.10,21 In addition, fees, that cannot be afforded, may be charged for access, discouraging low-income residents from participating in the use of CGs.22 Overall, financial barriers to entry, compounded with limited gardening knowledge, can make gardening a risky investment of time and money, especially for the new or inexperienced low-income gardeners.

Further compounding the obstacles between low-income residents and CGs is gentrification: a progressive displacement of a historic, low income residents. Gentrification has been correlated with increasing number of CGs in multiple studies, and increased urban green space accelerates the gentrification rate.1,23,24 Low-income neighborhoods were four times more likely to see improvements, such as reduced littering and increased neighborhood pride. However, these outwardly positive findings could also represent progressive gentrification. As property values increase, CGs in privately owned lots may find that their land has been reclaimed for development. Protective policies are rarely upheld, putting the gardens at risk of abrupt closure.25 Often, a CG is viewed as a “…temporary practice on a temporarily-available land” and are at risk of requisition.21 Given the marginal profits of selling CG produce, supplemental income from CG crops is unlikely to offset rising land values.5 So while many cities may attempt to foster CGs in low income communities, they may be unintentionally displacing the same populations that they are trying to support.26

Gentrification should be acknowledged, but efforts should made to include residents in civil planning to avoid uprooting such individuals from their homes.27 For instance, green space development should be coupled with affordable housing initiatives, with green space investment equally distributed across an urban community to improve maintenance of and proximity and transportation to the CGs.15 Though the majority of urban gardeners walk to their plots, those who do require transportation will only need to travel a short distance to the garden.28 In summary, if CGs are to fulfill their potential benefits of food stability, supplemental income, and personal and social development, low-income accessibility must be expanded.24

Insights for Further Investigation

Currently, the scope of literature focuses disproportionately on low income communities yet cannot determine if these populations have equitable access to CGs compared to their more affluent counterparts. In other words, we cannot say whether or not the community physically surrounding a community garden is in fact the people who are utilizing the community garden. It may be beneficial for future research to compare the socioeconomic traits of garden participants to the population of the community the garden is meant to serve. Further, most studies examine urban locales in the US or other western and developed countries. We recommend that further research addresses these gaps in the literature.

Acknowledgments:

Our sincere gratitude to Scholarly Communications Librarian, Ms. Kelly Hines, at the Pumerantz Library of Western University of Health Sciences, for her guidance in compiling this review. Kelly Hines has no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References:

- Guitart D, Pickering C, Byrne J. Past results and future directions in urban community gardens research. Urban Forestry and Urban Greening 2012;11(4):364-73 doi: 10.1016/j.ufug.2012.06.007[published Online First: Epub Date]|.

- Firth C, Maye D, Pearson D. Developing “community” in community gardens. Local Environment 2011;16(6):555-68 doi: 10.1080/13549839.2011.586025[published Online First: Epub Date]|.

- Carney PA, Hamada JL, Rdesinski R, et al. Impact of a community gardening project on vegetable intake, food security and family relationships: a community-based participatory research study. J Community Health 2012;37(4):874-81 doi: 10.1007/s10900-011-9522-z[published Online First: Epub Date]|.

- Bendt P, Barthel S, Colding J. Civic greening and environmental learning in public-access community gardens in Berlin. Landscape and Urban Planning 2013;109(1):18-30 doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2012.10.003[published Online First: Epub Date]|.

- Armstrong D. A Survey of Community Gardens in Upstate New York Implications for Health Promotion and Community Development. 2000;6:319-27

- Blair D, Giesecke, C., & Sherman, S. . A Dietary, Social and Economic Evaluation of the Philadelphia Urban Gardening Project. Journal of Nutrition Education 1991;23(4):161-67

- Korn A, Bolton SM, Spencer B, Alarcon JA, Andrews L, Voss JG. Physical and Mental Health Impacts of Household Gardens in an Urban Slum in Lima, Peru. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2018;15(8) doi: 10.3390/ijerph15081751[published Online First: Epub Date]|.

- He B, Zhu J. Constructing community gardens? Residents’ attitude and behaviour towards edible landscapes in emerging urban communities of China. Urban Forestry and Urban Greening 2018;34(June):154-65 doi: 10.1016/j.ufug.2018.06.015[published Online First: Epub Date]|.

- Kingsley JY, Townsend M, Henderson‐Wilson C. Cultivating health and wellbeing: members’ perceptions of the health benefits of a Port Melbourne community garden. Leisure Studies 2009;28(2):207-19 doi: 10.1080/02614360902769894[published Online First: Epub Date]|.

- Milliron BJ, Vitolins MZ, Gamble E, Jones R, Chenault MC, Tooze JA. Process Evaluation of a Community Garden at an Urban Outpatient Clinic. J Community Health 2017;42(4):639-48 doi: 10.1007/s10900-016-0299-y[published Online First: Epub Date]|.

- Algert SJ, Baameur A, Renvall MJ. Vegetable output and cost savings of community gardens in San Jose, California. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics 2014;114(7):1072-76 doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2014.02.030[published Online First: Epub Date]|.

- Filkobski I, Rofè Y, Tal A. Community gardens in Israel: Characteristics and perceived functions. Urban Forestry and Urban Greening 2016;17:148-57 doi: 10.1016/j.ufug.2016.03.014[published Online First: Epub Date]|.

- Foltz JL, Harris DM, Blanck HM. Support among U.S. adults for local and state policies to increase fruit and vegetable access. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 2012;43(3 SUPPL.2):S102-S08 doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.05.017[published Online First: Epub Date]|.

- Buckingham S. Women ( re ) construct the plot : the regen ( d ) eration of urban food growing. 2014;37(2):171-79

- Bussell MR, Bliesner J, Pezzoli K. UC pursues rooted research with a nonprofit, links the many benefits of community gardens. California Agriculture 2017;71(3):139-47 doi: 10.3733/ca.2017a0029[published Online First: Epub Date]|.

- Martinho da Silva I, Oliveira Fernandes C, Castiglione B, Costa L. Characteristics and motivations of potential users of urban allotment gardens: The case of Vila Nova de Gaia municipal network of urban allotment gardens. Urban Forestry and Urban Greening 2016;20:56-64 doi: 10.1016/j.ufug.2016.07.014[published Online First: Epub Date]|.

- Amato-Lourenco LF, Lobo DJA, Guimarães ET, et al. Biomonitoring of genotoxic effects and elemental accumulation derived from air pollution in community urban gardens. Science of the Total Environment 2017;575:1438-44 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.09.221[published Online First: Epub Date]|.

- van Holstein E. Relating to nature, food and community in community gardens. Local Environment 2017;22(10):1159-73 doi: 10.1080/13549839.2017.1328673[published Online First: Epub Date]|.

- Clarke LW, Jenerette GD. Biodiversity and direct ecosystem service regulation in the community gardens of Los Angeles, CA. Landscape Ecology 2015;30(4):637-53 doi: 10.1007/s10980-014-0143-7[published Online First: Epub Date]|.

- Haynes-Maslow L, Auvergne L, Mark B, Ammerman A, Weiner BJ. Low-income individuals’ perceptions about fruit and vegetable access programs: A qualitative study. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior 2015;47(4):317-24.e1 doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2015.03.005[published Online First: Epub Date]|.

- Drake LL, LJ. Validating verdancy or vacancy? The relationship of community gardens and vacant lands in the U.S. Cities 2014;40:133-42

- Althaus Ottmann MM, Maantay JA, Grady K, Fonte NN. Characterization of Urban Agricultural Practices and Gardeners’ Perspective in Bronx Community Gardens, New York City. Cities and the Environment 2016;5(1):1-27 doi: 10.15365/cate.51132012[published Online First: Epub Date]|.

- Maantay JA, Maroko AR. Brownfields to greenfields: Environmental justice versus environmental gentrification. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2018;15(10) doi: 10.3390/ijerph15102233[published Online First: Epub Date]|.

- Wolch JR, Byrne J, Newell JP. Urban green space, public health, and environmental justice: The challenge of making cities ‘just green enough’. Landscape and Urban Planning 2014;125:234-44 doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2014.01.017[published Online First: Epub Date]|.

- Petrovic N, Simpson T, Orlove B, Dowd-Uribe B. Environmental and social dimensions of community gardens in East Harlem. Landscape and Urban Planning 2019;183(November 2018):36-49 doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2018.10.009[published Online First: Epub Date]|.

- Litt JS, Schmiege SJ, Hale JW, Buchenau M, Sancar F. Social Science & Medicine Exploring ecological , emotional and social levers of self-rated health for urban gardeners and non-gardeners : A path analysis. Social Science & Medicine 2015;144:1-8 doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.09.004[published Online First: Epub Date]|.

- Pearsall H, Anguelovski I. Contesting and Resisting Environmental Gentrification: Responses to New Paradoxes and Challenges for Urban Environmental Justice. Sociological Research Online 2016;21(3):121-27 doi: 10.5153/sro.3979[published Online First: Epub Date]|.

- Morckel V. Community gardens or vacant lots? Rethinking the attractiveness and seasonality of green land uses in distressed neighborhoods. Urban Forestry and Urban Greening 2015;14(3):714-21 doi: 10.1016/j.ufug.2015.07.001[published Online First: Epub Date]|.

Article information:

Published Online: Oct 3rd, 2020.

IRB Approval: IRB was not needed as no patients were needed when conducting this research

Conflict of Interest Declaration: Authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding Source/Disclosure: No financial support was provided in the conduction of this research.