Steven D. Gay1, L.J. S. McKenzie, Christian L. Shafer1, Jordan R. Hilton1, S. Kathryn Potter, M.D.1.

PNWMSRJ. Published online April 13th, 2021.Introduction

The gallbladder is an organ that receives bile from the liver, stores and concentrates it, and contracts to release it when fatty foods enter the duodenum. In some individuals, concentrated bile can precipitate to form gallstones within the gallbladder—a condition known as cholelithiasis—from undissolved cholesterol or excess bilirubin. Contraction of the gallbladder can cause these stones to dislodge and block the cystic duct or other related bile ducts.A majority of patients are asymptomatic as the cholelithiasis never causes a blockage. However, a minority of individuals with cholelithiasis will have movement of the stones into their cystic duct, followed by inflammation and significant pain (cholecystitis), ultimately prompting the patient to seek medical treatment.

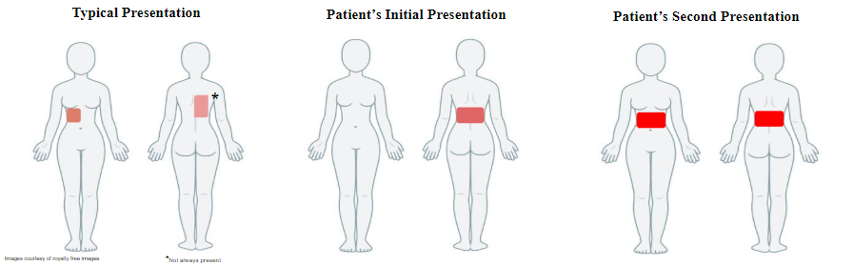

Typically, a patient with a complicated gallstone disease like cholecystitis will present with right upper quadrant pain (RUQ) that is severe, constant, and lasting several hours following meals, and accompanied by elevated liver enzymes, leukocytosis, gallbladder thickening and edema on imaging, and a positive Murphy’s sign.¹-3 The patient presented in this study fell outside some of these parameters yet still warranted consideration of cholecystitis as a possible cause of her abdominal and back pain.

Case Presentation

An otherwise healthy, 25-year-old Caucasian female, 2-months postpartum, presented to the urgent care clinic with a chief complaint of a 1-week history of achy, bilateral, mid-back pain, in a banding belt-like pattern that was most severe posteriorly, only present at night, and would wake her from sleep. She rated it 7-8/10 with no palliative or provoking factors and it would spontaneously resolve hours later. The patient denied pain while lying down, after meals, or with specific foods. She also denied dysuria, trauma, or previous episodes. Her BMI was normal, she was moderately active, and she ate a diet high in fruits and vegetables and low in fats.Physical exam was unremarkable except for mild tenderness in the RUQ. However, the patient had a negative Murphy’s sign.

The primary diagnosis at this point was gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), with a differential diagnosis of biliary colic.

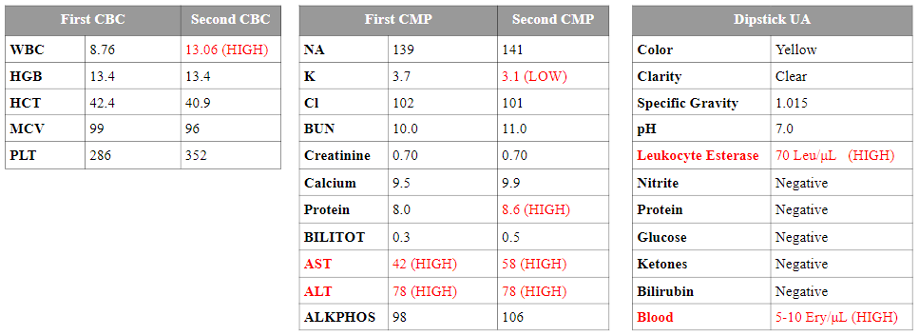

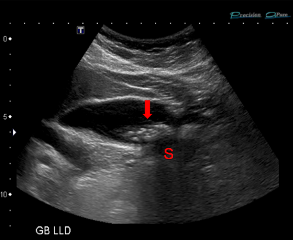

The patient was then referred to the emergency department (ED) for an ultrasound and laboratory testing. The gallbladder wall appeared normal with ultrasound, but stones were noted [Appendix Figure 1]. At this time, a complete blood count (CBC) and comprehensive metabolic panel (CMP) came back within normal limits except for mildly elevated liver enzymes [Appendix Table 1]. Urinalysis (UA) was unremarkable with the exception of elevated erythrocytes/μL and being positive for leukocyte esterase [Appendix Table 1]. After testing, the patient was sent home, instructed to monitor symptoms, and prescribed the proton pump inhibitor, omeprazole.

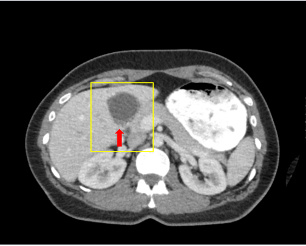

Unfortunately, the patient returned to the ED 2-hours later with severe back and stomach pain in a bilateral banding pattern that was equally painful anteriorly and posteriorly and rated as 10/10. She reported shortness of breath and an inability to get comfortable. Hydromorphone was administered twice, as the first dose was ineffective. A computerized tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis with oral contrast identified an edematous gallbladder with no other abnormalities [Appendix Figure 2]. Lab results now showed elevated (compared with the first sample) white blood count (WBC), protein (PROT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) [Appendix Table 1].

Upon this second visit, the differential shifted from GERD to acute calculous cholecystitis and the patient was admitted and scheduled for laparoscopic cholecystectomy the next day [Appendix Figure 3]. Postoperatively, the patient’s symptoms were completely resolved, and the patient has remained symptom-free.

Discussion

Uncomplicated gallstone diseases such as biliary colic typically present with RUQ pain that can radiate toward the right shoulder blade.¹ This pain usually lasts at least 30 minutes and subsides less than six hours later, and is thought to be associated with the gallbladder contracting and coming into contact with gallstones or sludge before relaxing. Laboratory test results are typically normal and abdominal examination typically yields a negative Murphy’s sign.Complicated gallstone diseases like cholecystitis present similarly to biliary colic with the addition of leukocytosis and elevated liver tests and a positive Murphy’s sign on exam. Gallbladder thickening and edema as well as a sonographic Murphy’s sign are to be expected. The pain in this situation is usually longer in duration, constant, and in the same location as with cholelithiasis.3

The recommended general management for patients presenting with symptoms related to gallstone disease is surgery versus nonsurgical management (such as medication) due to the high recurrence of painful symptoms.¹

This patient presented with pain patterns that followed an unexpected, bilateral, mid-back banding pattern that then escalated to include the anterior epigastric area at its peak [Appendix Figure 3]. As such, she was initially prescribed a proton pump inhibitor, omeprazole, with a primary diagnosis of GERD given her symptoms (nightly recurrence and substernal pain radiating to the back).4 The appearance of gallstones on ultrasound was not necessarily an indication that the patient’s symptoms were related as a large proportion of the population has stones that are asymptomatic [Appendix Figure 1].¹ Referral to an outpatient surgical clinic and education on the differential of biliary colic were warranted and provided.

Differential diagnoses of cystitis and nephrolithiasis should also be considered given that the UA showed abnormal values for leukocyte esterase and blood [Appendix Table 1]. Leukocyte esterase is typically an indicator for urinary tract infections in the presence of bacteriuria or the presence of nitrite, but this patient’s test yielded a negative nitrite result.5 While a urine culture and additional examination are recommended, a negative nitrite result suggests the possibility of a false positive from a contaminated sample. Microscopic hematuria was also noted, which makes nephrolithiasis a possibility given the concurrent severe back pain. Severe back pain could be confused with flank pain, but the bilateral nature and upper abdominal symptoms this patient demonstrated are not consistent with nephrolithiasis [Appendix Figure 3]. Finally, the patient’s CT scan more conclusively ruled out the presence of nephrolithiasis [Appendix Figure 2].

While the end result for this patient was resolution of her symptoms post-cholecystectomy, it is of note that the signature pain presentation of biliary colic or cholecystitis can be less localized than to the RUQ as demonstrated in this case. Early consideration of gallstone disease in patients presenting with bilateral back pain could limit the time patients are left suffering from their pain. However, this presentation is extremely uncommon according to the current literature, with no other cases identified by the researchers. In addition, back pain is the second most common patient reported complaint in a systematic review from 2016 that looked at 250,000 patients in 12 countries on 5 continents.6 Testing all patients with bilateral back pain for cholecystitis would lead to many patients enduring unnecessary tests and be costly to providers.

The utility of this case report is to encourage providers to maintain a broad differential in the event that more common causes of back pain are ruled out, especially when patient history, timing, pain patterns, and/or abdominal findings don’t fit the expected presentation.

Learning Points

- While cholecystitis will normally present with right upper quadrant pain that can radiate superiorly and posteriorly towards the right shoulder, an atypical bilateral location and banding pattern is possible as seen in this patient.

- Pain patterns should not be used to rule out diagnoses but should instead be considered a rule in criterion.

- Not all patients with back pain should be met with testing to rule out possible gallbladder etiology as this would neither be in the patient’s best interest nor cost effective. However, if no other cause for back pain is found on initial workup, less common pathologies, such as cholecystitis, should be considered.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to the patient and physicians at Samaritan Health Services for their cooperation and providing the images. This study was reviewed by the Western University of Health Sciences Institutional Review Board (Reference 1551993-1).References

- Trowbridge RL, Rutkowski NK, Shojania KG. Does this patient have acute cholecystitis? JAMA 2003; 289:80.

- Bridges F, Gibbs J, Melamed J, Cussatti E, White S. Clinically diagnosed cholecystitis: a case series. J Surg Case Rep. 2018;(2):rjy031. doi:10.1093/jscr/rjy03.

- Berhane T, Vetrhuys M, et al. Pain attacks in non-compilicated and complicated gallstone disease have characteristic pattern and are accompanied by dyspepsia in most patients: The results of a prospective study. Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology. 2006; 41:1, 93-101

- Vakil N, van Zanten SV, Kahrilas P, Dent J, Jones R, Global Consensus Group. The Montreal definition and classification of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a global evidence-based consensus. Am J of Gastroenterol. 2006;101(8):1900-1920.

- Devillé WL, Yzermans JC, van Duijn NP, Bezemer PD, van der Windt DA, Bouter LM. The urine dipstick test useful to rule out infections. A meta-analysis of the accuracy. BMC Urol. 2004;4:4. Published 2004 Jun 2. doi:10.1186/1471-2490-4-4

- Finley C, Chan D, et al. What are the most common conditions in primary care? Can Family Physician. 2018;64(11):832-840

Appendix

Appendix Table 1. Combined results of laboratory testing from patient’s first and second visits. Those highlighted in red were flagged as “HIGH” values by automated systems and were used in understanding the progression of the disease and forming a differential diagnosis.

Appendix Figure 1. Ultrasound image of the patient’s gallbladder with gallstone (arrow) visible. The stone appears hyperechoic (bright) and causes a hypoechoic (dark) shadow (S).

Appendix Figure 2. CT of the patient’s abdomen with oral contrast. Cholelithiasis with a distended gallbladder (yellow box) and a small volume of pericholecystic fluid (red arrow) were found.

Appendix Figure 3. Depictions of the typical pain pattern for gallstone pathology along with those presented by the patient at her initial and second visits (brighter red indicates more severe pain).

Article information:

Published Online: April 13th, 2021.

IRB Approval: Western University of Health Sciences Institutional Review Board (Reference 1551993-1).

Conflict of Interest Declaration: No conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding Source/Disclosure: No support was provided.