H Robert Cannon1 * , Brady Winfield1 *, Anthony Sainz1, Cade Cloward1, Rachel B Cannon MEd2, Elisabeth Guenther MD MPH1

Abstract

Purpose: We aim to determine if there has been an increase in marijuana-related suspensions (MRS) in an Oregon high school following marijuana legalization in 2015, and if students on an Individualized Education Plan (IEP) are more likely to be suspended for marijuana use compared to students who are not on an Individualized Education Plan (non-IEP). Methods: MRS data was collected retrospectively from a rural Oregon high school from 2012-2018. Student information was de-identified and separated into IEP and non-IEP populations. A 2-proportion z-test was used to compare the number of overall suspensions for pre vs. post-legalization. Results: In the 3 years prior to legalization there were 32 MRS, and 0.68% of students had a MRS. In the 3 years post-legalization, the number of MRS increased to 101, and 2.25% of students had a MRS (p<0.0001). Prior to legalization, there were 5 IEP MRS (0.84% of IEP students) and 27 non-IEP MRS (0.65% of non-IEP students) (p=0.406). Post-legalization there were 26 IEP MRS (3.8% of IEP students) and 75 non-IEP MRS (2.0% of non-IEP students) (p=0.0031). Conclusion: In the population studied, there was an increase in the percentage of students suspended for marijuana related offenses following marijuana legalization in 2015. The IEP students were more likely to receive a MRS compared to non-IEP students after marijuana legalization in this rural Oregon High School. Relevance Statement: Our study found a significant increase in marijuana-related suspensions (MRS) in the general student population with students on an Individualized Education Plan being the most strongly affected following recreational marijuana legalization in Oregon. As marijuana legalization becomes increasingly common across the United States it is imperative to monitor the impacts on students and youth.

Introduction

Marijuana legalization is becoming increasingly prevalent across the United States. Currently, 33 states have legalized medical marijuana with 10 states and Washington, D.C. having legalized recreational marijuana for adults over the age of 21. Concurrent with this increasing legalization, an increasing number of Americans also favor some form of marijuana use.1

In 2015, recreational marijuana was legalized in Oregon for adults over the age of 21. Research done in 2016 by the Oregon Health Authority through anonymous, school-based surveys of Oregon 8th and 11th grade students found that youth reported that marijuana was easier to obtain than cigarettes and about as easy to obtain as alcohol.2 In addition, parental approval of marijuana usage by youth has steadily increased since legalization in Oregon.3 Research has demonstrated that as acceptance of marijuana usage increases, overall usage of marijuana increases accordingly.4 Despite this information, little research exists regarding the impact on youth usage rates in states where recreational marijuana has been legalized for adults 21 and over.

Our group quantified the number of students suspended for marijuana possession in an Oregon high school both pre-legalization and post-legalization. Our first objective was to determine if there had been an increase in marijuana-related suspensions (MRS) across the entire student body post-legalization. Our second objective was to determine if students on an Individualized Education Plan (IEP, indicating some form of learning disability) were more likely to have a MRS compared to non-IEP students post-legalization. We pursued the second objective because youth with learning disabilities have been shown to be more susceptible to substance abuse.5,6 Compounding risk factors for substance abuse include academic trouble, loneliness, a desire to fit in and low self-esteem.7 Due to the increased availability of marijuana and the predilection of substance abuse for the IEP population,5,6 we hypothesized an increase in the number of MRS among all high school students post-legalization, and that IEP students would be more likely to receive a MRS compared to non-IEP students post-legalization.

Methods

We examined de-identified records for 9,214 students from one Oregon high school for six consecutive school years from 2012 to 2018. Choosing this specific six-year span allowed us to compare data points from three years prior to the legalization of recreational marijuana and three years post-legalization. Suspension policies remained unchanged during the three years before and after legalization. A student was suspended only if they were caught with marijuana in their possession on school property. Students caught with marijuana a second time during the school year were expelled rather than suspended so repeat offenders were not included in our data.

We used a 2-proportion z-test to compare the following: 1) the percentage of overall MRS pre-legalization vs. post-legalization, and 2) the percentage of MRS pre-legalization and post-legalization for IEP students vs. non-IEP students.

The high school of interest had an average enrollment of 1,500 students per year, 200 of which on average qualified for an IEP.

The methods used in this study were approved by the Western University of Health Sciences Institutional Review Board (P18/IRB/054).

Results

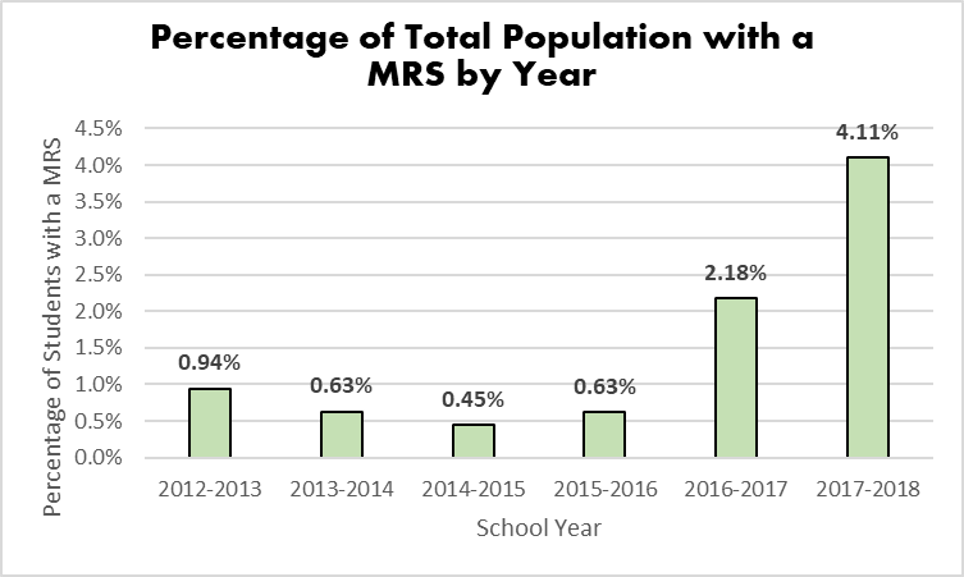

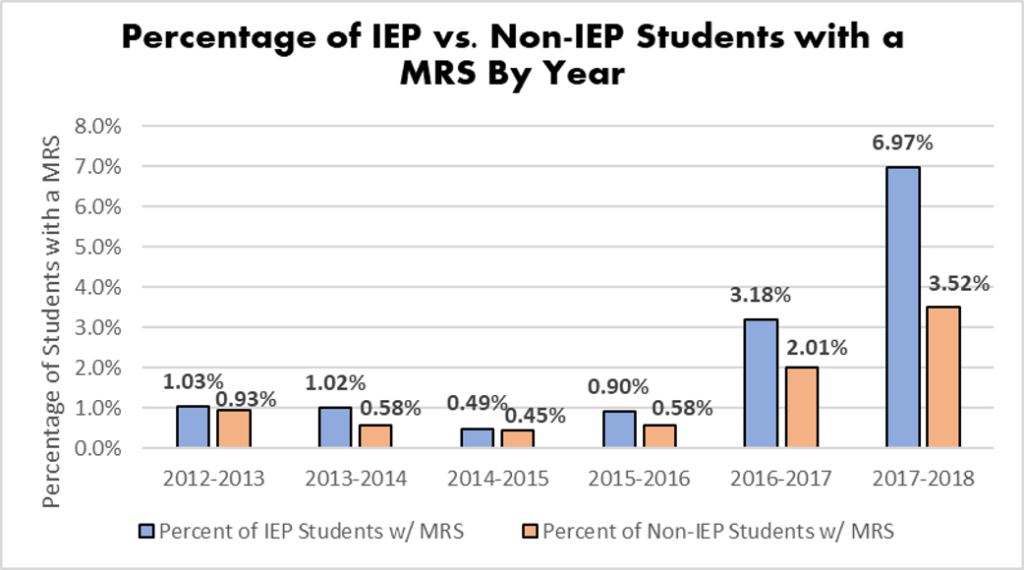

In the three years following legalization of recreational marijuana (2015-2018), we found a significant increase in MRS among all students (p<0.0001) (see Figure 1). Additionally, the increase in MRS was much greater among IEP students compared to non-IEP students post-legalization (p=0.0031) (see Figure 2).

Figure 1: From September 2012 to June 2015 (i.e. pre-legalization), there were 32 MRS among all students (0.68% of total student population). From September 2015 to June 2018 (i.e. post-legalization), the number of MRS among all students increased to 101 (2.25% of total student population). Students at this Oregon high school were more likely to have a MRS following recreational legalization (p<0.0001).

Figure 2: From September 2012 to June 2015, 0.83% of IEP students had a MRS compared to 0.65% of non-IEP students (p=0.406). From September 2015 to June 2018, 3.8% of IEP students had a MRS compared to 2.0% of non-IEP students. Students on an IEP had a significantly higher rate of MRS compared to their non-IEP peers post-legalization (p=0.0031).

Discussion

Previous studies have examined the effect of marijuana legalization on youth usage via self-reporting methods.2 Our data is unique because we used objective data from the school district to eliminate reliance on self-reporting. Our study cannot determine if students were consuming more marijuana post-legalization, but it indicated that students were more likely to be in possession of marijuana on school grounds post-legalization. In comparing the number of MRS before and after legalization, it appears that youth are being impacted by marijuana legalization in ways that can be quantified.

Following the legalization of recreational marijuana in Oregon, students on an IEP were suspended at a significantly higher rate compared to non-IEP students. This appears to be consistent with previous research suggesting a link between individuals with learning disabilities and increased risk of substance use problems.5 More research is needed regarding the link between marijuana legalization and increased MRS for IEP students as prior to legalization, IEP students were not suspended at a significantly higher rate than their non-IEP peers.

At the time of this study the school district had not made any changes in policy to address recent marijuana legalization. This makes us feel confident that our post-legalization data was not inflated by policies encouraging increased “policing” of students by faculty or administration in response to marijuana legalization.

Increased “policing” of students is likely not the most efficacious response to marijuana legalization, but it is important to consider modernizing policies or implementing programs to minimize the unwanted effects of increased marijuana availability in states where it is legal. For example, drug education as a way of preventing suspension can benefit all youth but may be particularly beneficial to students with learning disabilities.

Marijuana has been shown to negatively impact adolescents’ learning and decision-making abilities and is associated with early school leaving.8 Emerging research has suggested that suspensions or expulsions from school can negatively impact academic performance of a student.9 Education is one of the strongest predictors of health: the more education a student can receive, the better their health is likely to be in the future.10 Comprehensive drug education for youth may deter drug use and improve health outcomes.11,12,13

A pilot study in Washington state included two high schools and, as an alternative to out of school suspension for marijuana use, the students were required to complete an online in-school module designed to educate and stop illicit marijuana use.14 Over the course of the program, student knowledge about marijuana increased from 40% at the start to almost 90% when completed with 50% of students saying they would stop their current marijuana use14. Programs such as these show the value of using education as a deterrent as opposed to focusing on punishment (suspension) after the offense. In the rural Oregon high school we studied, the risk of out of school suspensions did not seem to be a deterrent for students bringing marijuana onto school grounds as the numbers of MRS increased each year after legalization.

Previous studies relying on self-reported data in Colorado, Washington, and Oregon have indicated decreased youth marijuana usage immediately post-legalization.15 Our data was consistent with these findings as we did not see a significant increase in MRS within the first year after legalization. However, when looking at data longitudinally across multiple years post-legalization, we discovered an increasing trend in MRS. Current literature may underestimate youth marijuana use and minimize the impact of marijuana legalization among youth.16 Working closely with school districts may help provide accurate and consistent estimates of underage marijuana use while minimizing reliance on self-reporting.

Our study was limited in that we were only able to gather data from one high school. We were also unable to obtain data regarding other causes for suspension (behavior, truancy, weapons, non-marijuana related drugs, etc.). Having this data in the future would help serve as an additional control to determine if all-cause suspensions have increased over this six-year period or if the increase is isolated to marijuana possession only. Future improvements will include surveying more high schools and collecting data related to all suspensions. Surveys to high school administrators will also be included with requests for data to determine what changes in administration have occurred over the six-year span as well as if any policy changes occurred during that time period.

Conclusion

We found a significant increase in the proportion of students with a MRS since marijuana legalization in this rural Oregon high school setting. IEP students were suspended at a significantly higher rate compared to their non-IEP peers post-legalization. These findings have significance for educators, parents, and providers who practice in states where recreational marijuana is legalized, as well as states considering legalizing recreational marijuana.

References

- McCarthy J. Record-High Support for Legalizing Marijuana Use in U.S. Gallup.com. https://news.gallup.com/poll/221018/record-high-support-legalizing-marijuana.aspx?g_source=Politics&g_medium=newsfeed&g_campaign=tiles. Published 2017.

- Dilley J. Oregon Marijuana Report. Apps.state.or.us. https://apps.state.or.us/Forms/Served/le8509b.pdf. Published 2016.

- Paschall MJ, Grube JW, Biglan A. Medical Marijuana Legalization and Marijuana Use Among Youth in Oregon. J Prim Prev. 2017;38(3):329-341.

- D’Amico E. Why Children Need to Be Shielded from Marijuana Ads. Rand.org. https://www.rand.org/blog/2018/06/why-children-need-to-be-shielded-from-marijuana-ads.html. Published 2018.

- Carroll Chapman SL, Wu LT. Substance abuse among individuals with intellectual disabilities. Res Dev Disabil. 2012;33(4):1147-56.

- Conrod, Patricia. “A Population-Based Analysis of the Relationship Between Substance Use and Adolescent Cognitive Development.” American Journal of Psychiatry, 3 Oct. 2018, ajp.psychiatryonline.org/doi/10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.18020202.

- Daw J. Substance abuse linked to learning disabilities and behavioral disorders. American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/monitor/jun01/disorders. Published 2001.

- Lynskey, M. and Hall, W. (2000), The effects of adolescent cannabis use on educational attainment: a review. Addiction, 95: 1621-1630. doi:1046/j.1360-0443.2000.951116213.x

- Evans-Whipp TJ, Plenty SM, Catalano RF, Herrenkohl TI, Toumbourou JW. Longitudinal effects of school drug policies on student marijuana use in Washington State and Victoria, Australia. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(5):994-1000.

- Freudenberg N, Ruglis J. Reframing school dropout as a public health issue. Prev Chronic Dis. 2007;4(4):A107.

- Mark Lemstra, Norman Bennett, Ushasri Nannapaneni, Cory Neudorf, Lynne Warren, Tanis Kershaw & Christina Scott (2010) A systematic review of school-based marijuana and alcohol prevention programs targeting adolescents aged 10–15, Addiction Research & Theory, 18:1, 84-96, DOI: 3109/16066350802673224

- Carol K. Sigelman, Cheryl S. Rinehart, Alberto G. Sorongon, Lisa J. Bridges, Philip W. Wirtz; Teaching a coherent theory of drug action to elementary school children, Health Education Research, Volume 19, Issue 5, 1 October 2004, Pages 501–513, https://doi.org/10.1093/her/cyg058

- McBride, N. , Farringdon, F. , Midford, R. , Meuleners, L. and Phillips, M. (2004), Harm minimization in school drug education: final results of the School Health and Alcohol Harm Reduction Project (SHAHRP). Addiction, 99: 278-291. doi:1111/j.1360-0443.2003.00620.x

- Barbosa-Leiker, Celestina & Shaw, Michele & Anderson, Cristina & L. Matthews, A. (2018). Alternatives to suspension for marijuana use: Assessing student and staff data.

- Ahrnsbrak R. National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Comparison of 2014-2015 and 2015-2016 Population Percentages (50 States and the District of Columbia), SAMHSA, CBHSQ. Samhsa.gov. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUHsaeShortTermCHG2016/NSDUHsaeShortTermCHG2016.htm. Published 2016. Accessed March 7, 2019.

- Dilley, J., Richardson, S., Kilmer, B., Pacula, R., Segawa, M. and Cerdá, M. (2019). Prevalence of Cannabis Use in Youths After Legalization in Washington State. JAMA Pediatrics, 173(2), p.192.

Article information:

Published Online: August 16, 2020

IRB Approval: The methods used in this study were approved by the Western University of Health Sciences Institutional Review Board (P18/IRB/054)

Conflict of Interest Declaration: All Authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding Source/Disclosure: No funding was solicited or granted for this research project. All members of the research team volunteered their time.