Doron Volcani1, Chaya Prasad MD MBA1

PNWMSRJ. Published online Oct 3rd, 2020.Abstract:

Many “extreme sports,” such as skateboarding, snowboarding, and wakeboarding, are known for different mental and physical health benefits. The objective of this review article is to summarize the distinctive health benefits provided by the extreme sport of surfing. Peer-reviewed journals regarding surfing’s health benefits were reviewed in terms of physical benefits, mental benefits, the impact surfing can have on individuals with disabilities, and the effects of outdoor vs. indoor exercise. The results showed increased cardiovascular and muscular fitness related to surfing, improvement in the mental-wellbeing of “at risk” young adults and veterans suffering from Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), significant health benefits for individuals with disabilities, and more positive mood from outdoor vs. indoor exercise. While these positive outcomes are promising, studies focusing on the health effects of surfing are limited, and the methodologies lack rigor. Thus, more studies utilizing sophisticated research designs could greatly expand our understanding of the ways surfing can enhance health and wellbeing in a wide range of individuals.

Introduction:

Surfing is a unique sport that centers on the ocean and the elements (examples: wind and tide) that produce waves. Its allure is international in scope, as shown in a 2012 study that estimated 35 million surfers worldwide. The distribution showed 13.5 million surfers in the United States, 6.5 million in Oceania, 6 million in Asia, 4.5 million in Europe, and 4.5 million in Africa, with a gender gap (81% male vs. 19% female); 60% of surfers were over the age of 24.1 In the United States, a 2011 survey showed the profile of the average surfer was a 34-year-old male, with a college education or above, and earned at least $75,000 per year. The average surfer had 16 years of surfing experience, and had surfed 108 times per year.2 Extreme sports have been recognized for numerous psychological health benefits, and forming a connection with nature. A 2019 qualitative study that gained insight into the lives of 8 extreme sport athletes analyzed themes of early childhood experiences, challenges of the outdoors, and varying emotions and reactions with nature. Commonalities between the athletes showed how extreme sports, while risky, provided the psychological benefits of increasing positive emotions, resilience, and life-coping skills, as well as a pro-environmental benefit of connecting with nature.3 Surfing has been categorized as an extreme sport internationally, however little data exists as to its specific health benefit. Although research surrounding the subject is limited and ever evolving, this article summarizes the current findings in the English literature. We also will summarize the strengths and weaknesses of this extreme sport.

Materials and Methods:

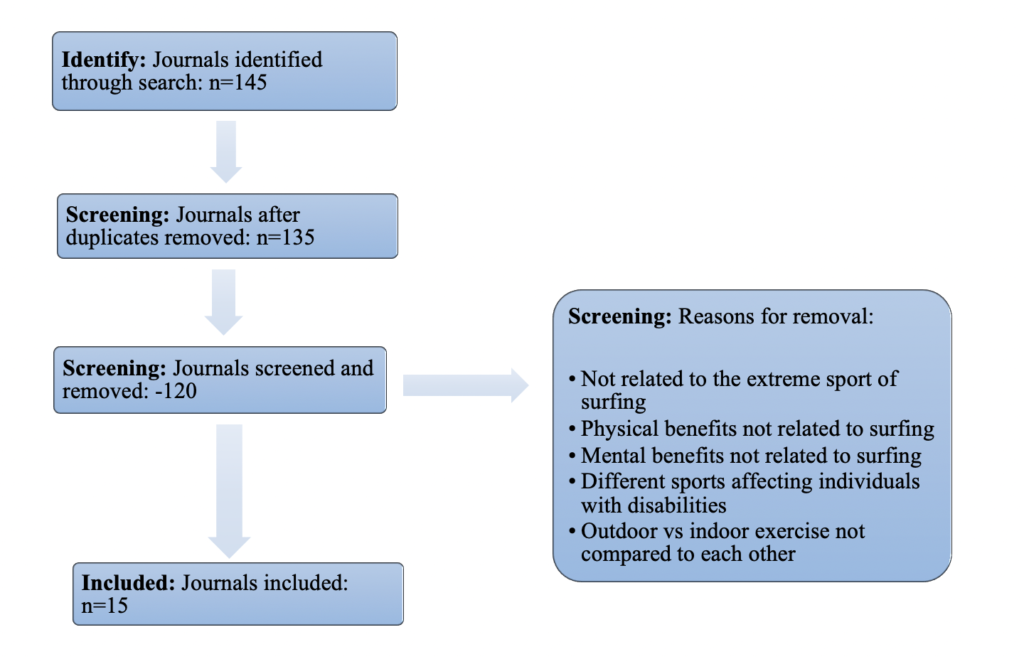

A literature search regarding surfing and its health benefits was conducted, providing a limited number of articles in peer-reviewed journals and websites. The databases used were Google for “surfer demographics,” PubMed, and Google Scholar. The years searched included 2010-2020, except for the search “surfing risks,” which included the years 2000-2020. Searched items included: “surfing,” “surfing benefits,” “outdoor exercise benefits,” “outdoor indoor exercise,” “surfing mental health,” and “surfing risks.” The reference lists from the searched articles were also screened for relevant information. No exclusion or inclusion criteria were put in place. The articles revealed themes related to surfing’s physical and mental benefits, impact on individuals with disabilities, and, more generally, the effects of outdoor vs. indoor exercise. A total of 145 journals were identified through this search, and after screening for duplicates and relatability, 15 journals were included in this article (Figure 1). This approach helped us gain information not only regarding surfing, but also related to the broad category of outdoor sports. The literature search provided articles from 2005 to 2020.

Figure 1. Schematic of literature search and journals included in this review article.

Results:

Physical Benefits of Surfing:

The physical demands of surfing are specific to the sport, however to date, only limited methods of directly comparing and measuring these aspects have been utilized. Authors Farley, Abbiss, and Sheppard4 noted physical data points during professional surf competitions. They measured male surfer’s heart rates, and utilized time-motion analysis, video recording, and Global Positioning Satellites (GPS), to focus on distinct aspects of surfing, such as paddling, resting, wave riding, breath holding, and recovery of the surfboard. Outcomes were influenced by the environmental and wave conditions that necessitated surfers to have high cardiorespiratory fitness, high muscular endurance, and increase in strength and anaerobic power, especially in the upper torso. Given the scant research data regarding the physical benefits of surfing, better measurements utilizing relevant performance analyses from other sports could provide a more detailed understanding of surfing’s dynamics.4

Mental Health Benefits of Surfing:

Authors Hignett, White, Pahl, Jenkin, and Le Froy5 provided insight into surfing and its ability to provide mental health improvements in children/young adults (between the ages of 12-16 years old) at risk of missing school or likely to be excluded from mainstream schooling. After a 12-week surfing program, there was self-reported increase in satisfaction in terms of self-evaluated physical appearance, more positive attitudes towards school and friendships, and greater environmental awareness. Furthermore, teachers gave these students more positive evaluations. Similarly, authors Caddick, Smith, and Phoenix6 found improved mental health outcomes related to surfing for veterans with PTSD. More specifically, employing dialogical narrative analysis with combat veterans belonging to a UK-based surfing charity, surfing was found to create a sense of respite from PTSD, and, as stated by the authors, “A full release from suffering due to surfing.” Analogous findings were shown in another prospective study of veterans with PTSD who were transitioning to civilian life. The authors evaluated attendance rates and retention in the program that included 5 surf sessions over 5 weeks. 14 veterans were enrolled, 11 completed the study, and 10 attended more than 3 sessions. Participants reported clinically meaningful improvements in PTSD severity and depressive symptoms.7

Surfing’s Benefits in Individuals with Disabilities:

A study performed in Portugal utilizing individuals with disabilities demonstrated that adapted surfing (customized to the needs of individuals with disabilities) promoted inclusivity and disability awareness in the general population. The authors assessed four factors: empowerment, social interaction and integration, physical rehabilitation, and disability awareness-raising, and analyzed the effects adapted surfing had on physical, mental, and social rehabilitation, and promoting inclusivity. Four major conditions were also identified, aquatic environment, environment-individual interaction, individual-coach/therapist interaction, and group interaction, which added value for adapted surfers. Findings demonstrated enhancement of self-esteem, increase in time spent exercising, greater teamwork and social inclusion, and an increase sense of protection toward the environment.8 In children with disabilities such as autism, Down syndrome, global developmental delays, and cerebral palsy, surfing effectively improved physical fitness. One group of authors evaluated seventy-one children who were divided into two groups, an eight-week surfing therapy group and an unstructured pool playgroup, and compared various physical fitness measures. Significant improvements to varying physiological measures were shown, including core strength, upper body strength, flexibility and cardiorespiratory endurance, body fat percentage and fat free mass, and bone mineral density.9 In another small study, researchers analyzed 10 children with grade 1 or 2 disabilities who did not exercise regularly, and compared physiological improvements before and after aquatic exercise. They found significant differences in lean body weight, muscular strength and endurance, cardiovascular endurance, flexibility, as well as differences in triglyceride and immunoglobulin G, demonstrating physical and immunological improvements to health.10

Benefits of Outdoor vs. Indoor Exercise:

One systematic review of the effects of outdoor vs. indoor exercising performed in 2011, examined eleven trials. Eligible controlled trials (randomized and non-randomized) must have compared the effects of outdoor exercise to indoor ones and reported one additional physical or mental benefit in either adults or children. Findings demonstrated that exercising in natural environments was associated with increased feelings of revitalization and positive engagements, more energy, and a decrease in tension, confusion, anger, and depression. Additionally, in the outdoor sample, there was greater enjoyment and satisfaction, and intent to repeat the activity again. While promising, the results were essentially based on self-reported measures of mental wellbeing.11 A more recent 2019 systematic review comparing the effects of exercise, in the presence of nature, on physical and mental wellbeing found that outdoor exercises may favorably influence affective valence and enjoyment, but it did not affect emotion, perceived exertion, exercise intensity, or biological markers. This review also screened for articles that must have compared the effects of outdoor vs indoor exercise and demonstrated one additional physical or mental benefit, which included comparative or crossover design trials. Overall, there was limited evidence that outdoor exercise showed greater benefits compared to exercise without exposure to nature.12 In the former systematic review, eleven trials were compared and totaled to 833 adults, while the latter’s reviewed twenty-eight trials.11,12 The contradictory findings demonstrate a need for large, well-designed, long-term trials in populations who would benefit the most.11 Authors Walter et al. are conducting an ongoing study that compares outdoor activities (such as hiking) to water activities (such as surfing) in active duty service members with major depressive disorder (MDD).13 While the results of the study are yet to be published, the strength of this article is in the methods utilized to conduct the study, such as the use of randomized controls to evaluate the differences in these natural settings, isolating the effect water has on the participants’ outcomes, and maximizing generalizability. The data employed a variety of modalities having complementary strengths and limitations. The 3-month follow-up, which to date is the longest for any surf therapy, is yet to be published. The results likely will provide a wide range of outcomes, potentially augmenting much of the previous research on the immediate and long-term effects of both hike and surf therapy.13

Discussion:

Surfing is a unique extreme sport practiced internationally, which has shown to provide physical and mental benefits, and enhances a connection with the environment. The authors reviewed the related publications in the English literature and relevant websites, and have summarized the above-mentioned benefits. Although there are limitations on the availability and methodologies in studying surfing’s benefits, the initial investigations showed surfing does help in unique ways. However, no discussion would be complete without highlighting some of the risk factors associated with surfing. Both benefits and risk factors are discussed below.

Benefits associated with surfing:

Surfing demands distinct muscles and cardiovascular requirements strictly related to its practice. Mentally, those “at risk” for lack of schooling as well as veterans with PTSD and possibly MDD mentally benefited after experiencing surfing. In individuals with disabilities, surfing was a useful method of improving mental and physical wellbeing. On a broader scope, one of surfing’s characteristics, occurring outdoors, appears to be an added reason for increased positive mood and enjoyment as compared to indoor exercise. An ongoing study, in veterans suffering from MDD, aims to answer some of the limitations of the research by investigating the benefits of outdoor activities vs. water activities such as surfing. This has been discussed in detail in the section highlighting outdoor vs. indoor exercise benefits.

Risks associated with surfing:

Though the benefits of surfing outweigh the risks, one should acknowledge them. Authors Zoltan, Taylor, and Achar, and Tseng and Jiang discuss the following risks, which include trauma, marine hazards, and environmental hazards.15,16 Sprains, strains, lacerations, and fractures are the most common type of trauma, usually resulting from the rider’s own surfboard. Marine hazards include jellyfish stings, stingrays, coral reefs, and occasional shark attacks. Environmental hazards include auditory exostoses, tympanic membrane rupture, otitis externa, and increase incidents of skin cancer risk from sun exposure.14 An additional environmental hazard includes gastrointestinal illness risks from fecal bacteria contaminated coastal waters, in urbanized areas. Furthermore, surfers were at greater risk compared to swimmers of ingesting larger amounts of water.15

The authors note that despite limited risk factors associated with surfing, there is overwhelming recent evidence of the physical and mental health benefits, especially in disadvantage populations such as young people at risk of exclusion from mainstream schooling, veterans suffering from PTSD and MDD, and individuals with both physical and mental disabilities. It is important to note that the major limitation of this review article is the limited publications in the English literature. In addition, most of the studies did not have control groups, or a long-term follow up. Given that extreme sports such as surfing could provide physical activity interventions in the disadvantaged populations, additional research is required to substantiate these benefits.

Acknowledgments:

I thank Dr. Chaya Prasad for her discussions and revisions, Dean Crone for providing the opportunity to participate in the Lifestyle Medicine Track, and WesternU COMP for providing the resources for making this paper possible.

References:

- Editor at SurferToday.com. How many surfers are there in the world? Surfertoday.com. https://www.surfertoday.com/surfing/how-many-surfers-are-there-in-the-world. Accessed July 24, 2020.

- Scott Wagner G, Nelsen C, Walker M. A socioeconomic and recreational profile of surfers in the United States A report by surf-‐first and the surfrider foundation. Surfrider.org. https://public.surfrider.org/files/surfrider_report_v13.pdf. Accessed July 24, 2020.

- MacIntyre TE, Walkin AM, Beckmann J, et al. An exploratory study of extreme sport athletes’ nature interactions: From well-being to pro-environmental behavior. Front Psychol. 2019;10:1233.

- Farley ORL, Abbiss CR, Sheppard JM. Performance analysis of surfing: A review. J Strength Cond Res. 2017;31(1):260-271.

- Hignett A, White MP, Pahl S, Jenkin R, Froy ML. Evaluation of a surfing programme designed to increase personal well-being and connectedness to the natural environment among ‘at risk’ young people. J Adventure Educ Outdoor Learn. 2018;18(1):53-69.

- Caddick N, Smith B, Phoenix C. The effects of surfing and the natural environment on the well-being of combat veterans. Qual Health Res. 2015;25(1):76-86.

- Rogers CM, Mallinson T, Peppers D. High-intensity sports for posttraumatic stress disorder and depression: feasibility study of ocean therapy with veterans of Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation Iraqi Freedom. Am J Occup Ther. 2014;68(4):395-404.

- Lopes JT. Adapted Surfing as a Tool to Promote Inclusion and Rising Disability Awareness in Portugal. Journal of Sport for Development. 2015; 3(5):4-10.

- Clapham ED, Lamont LS, Shim M, Lateef S, Armitano CN. Effectiveness of surf therapy for children with disabilities. Disabil Health J. 2020;13(1):100828.

- Kim K-H, Lee B-A, Oh D-J. Effects of aquatic exercise on health-related physical fitness, blood fat, and immune functions of children with disabilities. J Exerc Rehabil. 2018;14(2):289-293.

- Thompson Coon J, Boddy K, Stein K, Whear R, Barton J, Depledge MH. Does participating in physical activity in outdoor natural environments have a greater effect on physical and mental wellbeing than physical activity indoors? A systematic review. Environ Sci Technol. 2011;45(5):1761-1772.

- Lahart I, Darcy P, Gidlow C, Calogiuri G. The effects of green exercise on physical and mental wellbeing: A systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(8):1352.

- Walter KH, Otis NP, Glassman LH, et al. Comparison of surf and hike therapy for active duty service members with major depressive disorder: Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial of novel interventions in a naturalistic setting. Contemp Clin Trials Commun. 2019;16(100435):100435.

- Zoltan TB, Taylor KS, Achar SA. Health issues for surfers. Am Fam Physician. 2005;71(12):2313-2317.

- Tseng LY, Jiang SC. Comparison of recreational health risks associated with surfing and swimming in dry weather and post-storm conditions at Southern California beaches using quantitative microbial risk assessment (QMRA). Mar Pollut Bull. 2012;64(5):912-918.

Article information:

Published Online: Oct 3rd, 2020.

IRB Approval: IRB approval was not required.

Conflict of Interest Declaration: There are no conflicts of interest.

Funding Source/Disclosure: No financial support was provided.